“Grief darkened my heart.” Everything on which I set my gaze was death. My home town became a torture to me; my father’s house a strange world of unhappiness; all that I had shared with him was without him transformed into cruel torment. My eyes looked for him everywhere, and he was not there. I hated everything because they did not have him, nor could they now tell me ‘look, he is on his way,’ as used to be the case when he was alive and absent from me. I had become to myself a vast problem, and I questioned my soul, “Why are you sad, and why are you very distressed?” But my soul did not know what reply to give.

-Augustine of Hippo, Book VI, The Confessions

Thagaste, North Africa: 374-376 AD

For a brief moment in his life, Augustine of Hippo must have thought his star was rising. He had spent his teens studying rhetoric and the great classical writers such as Cicero and Virgil in the city of Carthage. Although he long ago swore that the search for ultimate wisdom would be his primary motivation in life, the lure of temporal success was just too hard to resist.

And now he was back in his hometown of Thagaste, a bona fide teacher of rhetoric. In a world where the art of verbal persuasion was the primary means to gather the favor of both the mighty and the masses, one could see why a highly skilled rhetorician would be in great demand. In his own words:

Overcome with greed myself, I used to sell the eloquence that would overcome an opponent.

He had also made friends in Carthage, intellectuals whose thoughts must have inflamed and inspired his ever curious mind in ways that the inhabitants of sleepy backwater Thagaste never could. They had introduced him to the doctrines of the Manichees, a religion that emanated from ancient Persia which stated that the world was the creation of a god of good and a god of evil. Their philosophizing nature and grand cosmological speculations made his mother’s simple Christian faith seem rather…..dull. Besides, he had read the Bible in its Latin translation and it couldn’t compare at all with the verse and language of Cicero’s writings. What possible wisdom could they hold?

Upon his return to Thagaste, Augustine became reacquainted with a friend of his youth.

During those years when first I began to teach in the town where I was born, I had come to have a friend who because of our shared interests was very close. He was my age, and we shared the flowering of youth. As a boy he had grown up with me, and we had gone to school together and played with one another.

…..

It was a very sweet experience, welded by the fervour of our identical interests.

Bearing with him all the wisdom and knowledge he had acquired from Carthage, Augustine a fide deflexeram, or wrenched his friend from his faith in Christianity as a kind of service. However, one day his friend became very ill – so much so that his parents had opted to baptize him in order to receive a remission of his sins if he were to die. Augustine didn’t take this situation seriously and joked about it upon his friend’s recovery. Much to his surprise, his friend took his baptism quite seriously and asked Augustine to be respectful of his decision.

But our sharp little rhetorician thought all he had to do was bid his time. Augustine would set his friend straight and everything would be right in the world….

…..and then his friend died….

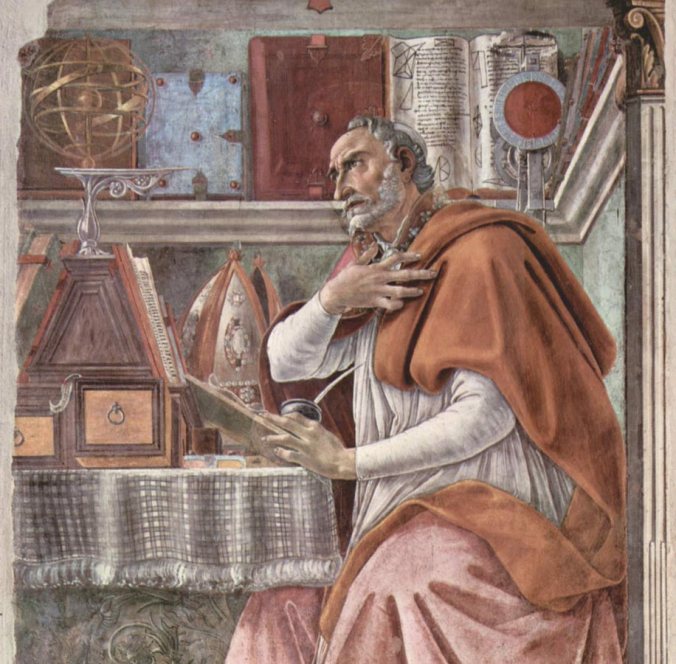

The First Mourning by William Adolphe Bouguereau

—————————————————————————–

The opening quotation at the top of this blog was Augustine’s immediate reaction to the death of his close but unnamed friend. Suffice it to say – he took the loss quite hard. However we must remember that the Confessions are written in two voices: that of the young man experiencing these emotions at the time, and the much older adult who has started to reflect on these experiences.

Augustine the Twenty-something Rhetoritician describes his thoughts as:

I was surprised that any other mortals were alive, since he who I had loved as if he would never die was dead. I was even more surprised that when he was dead, I was still alive, for he was my “other self.” Someone has well said of his friend, “He was half my soul.” I had felt that my soul and his were ‘one soul in two bodies.” So my life was to me a horror. I did not wish to live with one half of myself, and perhaps the reason why I so feared death was that then the whole of my much loved friend would have died.

It was, as the youth of today would call it, a “bromance.”

Had we been alive at the time, to have seen the whiz-kid genius and his ever present wingman laughing in the marketplaces, debating in the streets, and chasing after the virtue of young maidens – I have no doubt that many of us would have been moved by young Augustine’s great sorrow.

And yet, Older Augustine has a different perspective:

At that time I wept very bitterly and took my rest in bitterness. I was so wretched that I felt a greater attachment to my life of misery than to my dead friend. Although I wanted it to be otherwise, I was more unwilling to lose my misery than him, and I do not know if I would have given up my life for him as the story reports of Orestes and Pylades, who were willing to die for each other together, because it was worse than death to them not to be living together. But in me emerged a very strange feeling that was the opposite of theirs. I found myself heavily weighed down by a sense of being tired of living and scared of dying. I suppose that the more I loved him, the more hatred and fear I felt for the death which had taken him from me, as if it were my most ferocious enemy. I thought that since death had consumed him, it was suddenly going to engulf all humanity.

And so Augustine the Bishop raises an important question with his revelation.

Was he really grieving for his friend?

Or was he grieving for himself? Was he actually grieving about the loss that Death had inflicted on his life?

One modern commentator couldn’t help but remark that perhaps Young Augustine was probably entertaining thoughts such as “How dare this guy die and leave -me- in a state like this?”

Our Older Augustine uses this personal episode of sorrow as a starting point to examine the nature of grief and the grieving process. And behind this dissection of grief is a theory about the nature of friendship.

Augustine follows in the footsteps of ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and Cicero who defined friendship as a form of love. For Augustine, all forms of Love seeks or attempts to Unite You with Something Else. The enjoyment of Love is when you have been united with the thing you were seeking.

In terms of friendship, it would be appropriate to say then that this is the state when one person’s inner being (soul, psyche, etc.) is united with another. Two souls may become one. Or multiple for that matter.

While undoubtedly there is a penchant to interpret this in a Romantic sense, I’d ask you gentle reader to consider the following example: sports teams. One of my own friends, who likes to reminiscence about his glory days on a high school American football team, would often describe a kind of feeling when “our team was staring with one gaze at our opponents down field.” Even an observer can usually tell when a particular group of people might share a certain sort of chemistry in their interactions.

Friendship then is that sense of shared unity. But what happens when that unity is disrupted? Or destroyed?

I was in misery, and misery is the state of every soul overcome by friendship with mortal things and lacerated when they are lost. Then the soul becomes aware of the misery which is its actual condition even before it loses them.

For Augustine, Grief then is that agony when those souls are torn in two. When that beautiful unity is ripped asunder and you are left broken by it. This might be the appropriate time to recall the idea of a Romantic relationship, or rather the End of a Romantic relationship.

But notice how Augustine defines misery – “a state of every soul overcome by friendship with mortal things.” The soul or psyche just doesn’t realize it is in such a state of misery until the loss of the mortal thing. As he states later on in Book IV of the Confessions:

The reason why that grief had penetrated me so easily and deeply was that I had poured out my soul on to the sand by loving a person sure to die as if he would never die.

In other words, the feeling of grief is the natural outcome of expecting some sort of endless happiness from a mortal and finite thing. For those who might be familiar with the teachings of the Siddartha Gautama, Augustine’s insight mirrors the Buddhist idea of the First Noble Truth – that all conditional phenomena and experiences are not ultimately satisfying and will bring about suffering.

One could say that Augustine’s grief at the loss of his friend was due to the fact that Augustine had loved inappropriately. Or to utilize some Platonic logic, how can something that is impermanent bring about a form of permanent happiness? It can only result in a misery at the end.

The lost life of those who die becomes the death of those still living.

Friendship is the most valuable thing to have on this Earth, or so the ancient philosophers said. Is there some way to honor and acknowledge it without going through a period of excessive loss?

So what is our dear Bishop of Hippo’s solution? He offers a simultaneous religious and Platonic answer: To love our friends in God.

Happy is the person who loves you [God], and his friend in you, and his enemy because of you. Thought left alone, he loses none dear to him; for all are dear in the One who cannot be lost.

From a Platonic perspective, there is only One thing that is Truly Permanent. The Beauty that makes us love things, places, and individuals is merely a small reflection of that One Thing which is the source of all that Beauty.

A Christian believer would phrase this in the way Augustine did:

O God of hosts, turn us and show us your face, and we shall be safe. For wherever the human soul turns itself other than you, it is fixed in sorrows, even if its fixed upon beautiful things external to you and external to itself, which would neverthless be nothing if they did not have their being from you.

As was stated before, friendship is an act of unity. So for Augustine, to “love our friends-in-God,” is to essentially share an eternal happiness with our friends, who if departed from us are kept safe by that One Permanent Thing.