In my previous post Turn Inward: Augustine On Grief, I had mentioned a bit of Augustine of Hippo’s idea about the nature of friendship and its relationship to the feeling of grief.

It should be noted that Augustine’s idea of friendship is indebted to the tradition of Graeco-Roman thought and specifically to one Marcus Tullius Cicero.

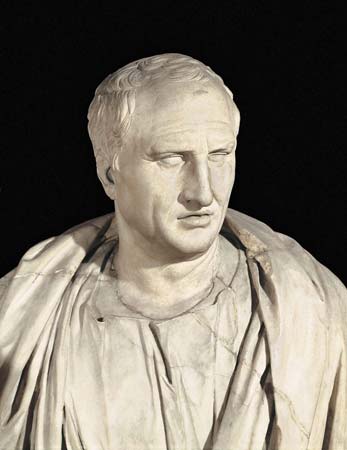

Cicero, who lived 300+ years before Augustine of Hippo, was one of the most celebrated figures of the last days of the ancient Roman Republic. He was Rome’s greatest Orator as well as being a philosopher, politician, and lawyer. His contemporaries were the likes of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, whom he struggled against in one form or another during the Roman civil war.

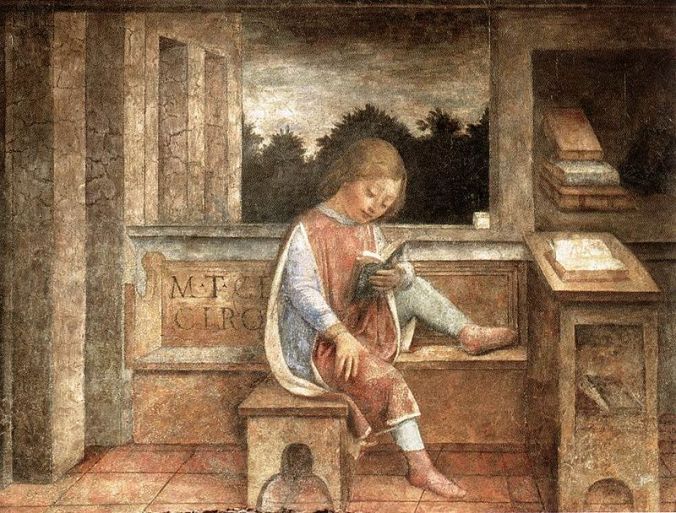

The Young Cicero Reading by Vincenzo Foppa, 1464

One method by which Cicero popularized the subject of philosophy in ancient Rome was through his writing of dialogues. I wanted to take the opportunity to examine one of these dialogues entitled – Laelius de Amicitia, often translated as On Friendship, which Augustine undoubtedly read as part of his preliminary education.

The principal speaker in the dialogue is Gaius Laelius Sapiens, a statesman, general and hero of ancient Rome. His two son in laws, Gaius Fannius and Quintus Scaevola (one of Cicero’s teachers) are speaking with him about the death of Laelius’ good friend Scipio Africanus, the greatest consul and general of his generation. Laelius and Scipio’s fantastic friendship was well known to the Roman people, and so his comments on what constitutes friendship carries great weight.

And so through Laelius, Cicero is able to elucidate his conceptions on friendship.

Let’s take a look at some of the highlights.

1.) Friendship can only exist between good men.

This may sound rather counter-intuitive to most people. After all, robbers, thieves, brigands all have friends. In fact, the Greek philosopher Aristotle in Books 8 and 9 of the Nichomachean Ethics has 3 categories of friendship – Ones of Pleasure, Ones of Utility, and Ones of Virtue.

The first two are very fleeting, the last type based on virtue can last till death.

It is that last type that Cicero has identified as real and true friendship, hence that friendship can only exist between “good” men. What does he mean by good?

We mean then by the “good” those whose actions and lives leave no question as to their honour, purity, equity, and liberality; who are free from greed, lust, and violence; and who have the courage of their convictions.

2.) Friendship is defined as “a complete accord on all subjects human and divine, joined with mutual good will and affection.”

Cicero makes it a point to praise this sort of Friendship above all material gain in the world, which he states is merely due to the capriciousness of fortune. Only Wisdom in his mind ranks about Friendship. He considers Virtue to be the “parent and preserver” of Friendship, without which friendship cannot possibly exist.

Although this sort of profit can bring about many useful advantages, that is not the soul purpose of friendship. As he states:

What can be more delightful than to have some one to whom you can say everything with the same absolute confidence as to yourself? Is not prosperity robbed of half its value if you have no one to share your joy? On the other hand, misfortunes would be hard to bear if there were not some one to feel them even more acutely than yourself. In a word, other objects of ambition serve for particular ends – riches for use, power for securing homage, office for reputation, pleasure for enjoyment, health for freedom from pain and the full use of the functions of the body. But friendship embraces innumerable advantages. Such friendship enhances prosperity, and relieves adversity of its burden by halving and sharing it.

3.) Friendship’s primary good is the fact that “it gives us bright hopes for the future and forbids weakness and despair.”

In the face of a true friend a man sees as it were a second self. So that where his friend is he is; if his friend be rich, he is not poor; though he be weak, his friend’s strength is his; and in his friend’s life he enjoys a second life after his own is finished. This last is perhaps the most difficult to conceive. But such is the effect of the respect, the loving remembrance, and the regret of friends which follow us to the grave. While they take the sting out of death, they add a glory to the life of the survivors.

4.) Friendship transcends the search for material advantages.

For as to material advantages, it often happens that those are obtained even by men who are courted by a mere show of friendship and treated with respect from interested motives. But friendship by its nature admits of no feigning, no pretence: as far as it goes it is both genuine and spontaneous. Therefore I gather that friendship springs from a natural impulse rather than a wish for help: from an inclination of the heart, combined with a certain instinctive feeling of love, rather than from a deliberate calculation of the material advantage it was likely to confer.

If we accept this four propositions regarding friendship to be true, than the rest of Cicero’s advice becomes rather obvious for those intent on securing this higher form of friendship.

- Never make disgraceful requests or grant them for your friends.

- In the friendships of virtuous and upright people – unrestricted communication should exist.

- And above all – be careful on how one chooses his or her friends. At minimum, one should seek out people with qualities of firmness, stability, and constancy.

It is that last bit, about how we should go about choosing our friends, which we should remember when we take a peek later on in Augustine’s accounts of how he formed his early and rather unwise friendships.

Now what is the quality to look out for as a warrant for the stability and permanence of friendship? It is loyalty. Nothing that lacks this can be stable. We should also in making our selection look out for simplicity, a social disposition, and a sympathetic nature, moved by what moves us. These all contribute to maintain loyalty. You can never trust a character which is intricate and tortuous.