Before I get started on this bit of the “Agrarian Doubts” series, I wanted to remind my gentle readers of a pointed fact: Not until the 1950s with the advent of William F. Buckley’s National Review, could it ever be said that there was such a thing as a “Conservative movement” within the United States. This is unlike the case in Great Britain, where the Tory party has more or less since its inception represented Anglo-American conservative values.

This will sound strange to modern ears, since in our current environment to be a Republican is to be some type of Conservative and to be a Democrat is to be some type of liberal. However, this wasn’t always the case. You had liberal and conservative philosophies, sometimes with a distinct regional character, mixed into the agenda of political parties that were divided on other issues.

Such is the situation with Jeffersonian Democracy in the American South. On the one hand, Thomas Jefferson is often claimed by modern day Democrats as one of their own given the lineage of the party. This may also have to do with the fact that Jefferson’s personal beliefs on religion, science, and political freedom is compatible with modern liberal politics in a way that say… Andrew Jackson’s views are not.

One of the issues that can be considered a strain of Southern Conservatism supported by Jefferson’s party would be the concern for the yeoman farmer. Jefferson’s political inheritors in the South often chaffed at the Federalists party’s attempt to give power to a centralized government and to diversify the economy in aid to Northern industrialists.

Like their landed gentry cousins in Great Britain, the Southern plantation owner viewed himself as an aristocrat and brooked no interference in his traditional way of life. In their mindset, the United States was first and foremost a farmer’s republic. Following Jefferson’s own views, many southerners believed that farmers were intrinsically more virtuous than city dwellers.

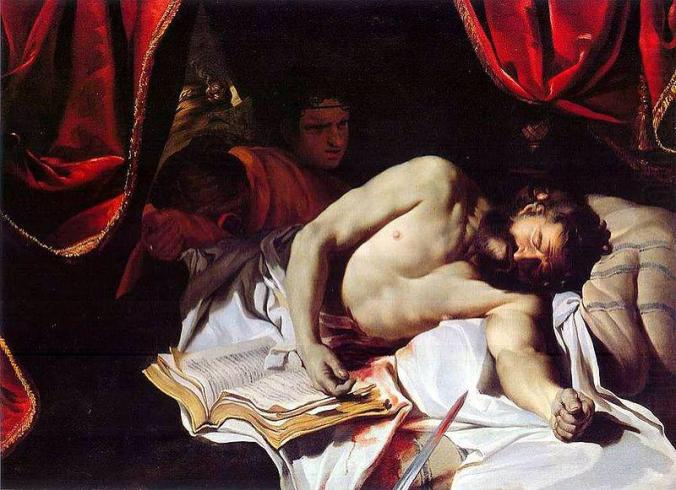

This a rather ancient opinion, older than the United States, older than Great Britain. It is an opinion that is even older than Christianity in the West. One need only look back at the historical experiences of both the Roman Republic and Athenian Democracy to see its roots. Up until the modern era, there has always been a kind of social distrust of merchants who didn’t make a living working off the land.

This opinion isn’t even limited to Western culture, as China, Japan, and Korea traditionally placed merchants at the bottom of the Confucian social hierarchy.

And where do merchants congregate? Where does the use of money to make even more money occur?

It happens in Cities where the excess of wealth gives rise to other jobs that are also not connected to the land. This concentration of people also comes with an increase of crime and vice in the locality.

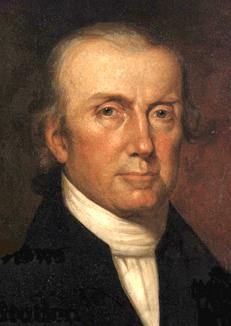

Such was the opinion of many southerners, especially intellectuals like John Taylor of Caroline, Virginia. Taylor wrote a kind of encomium to the wonders of rural life in his rather dense work known as the Arator. The Arator is a collection of philosophical, practical, and political essays on the nature of agriculture. In one line on the act of farming, Taylor waxes poetic saying that in farming:

the practice of every moral virtue is amply remunerated in this world, whilst it is also the best surety for attaining blessings of the next.

Or to put it plainly – Farming makes life better and it will secure your afterlife as well.

Predictably, Taylor contrasted the bucolic nature of rural life against the forces of industrialization – “the stock jobbers, the banks, the paper money party, the tariff-supported manufacturers.” These corrupt industrialists would be the undoing of the virtue necessary to maintain the landowner society that is the republic. Invoking an ancient theme as old as Rome itself, without civic virtue there would be no way for a republic to safeguard its political independence and freedom.

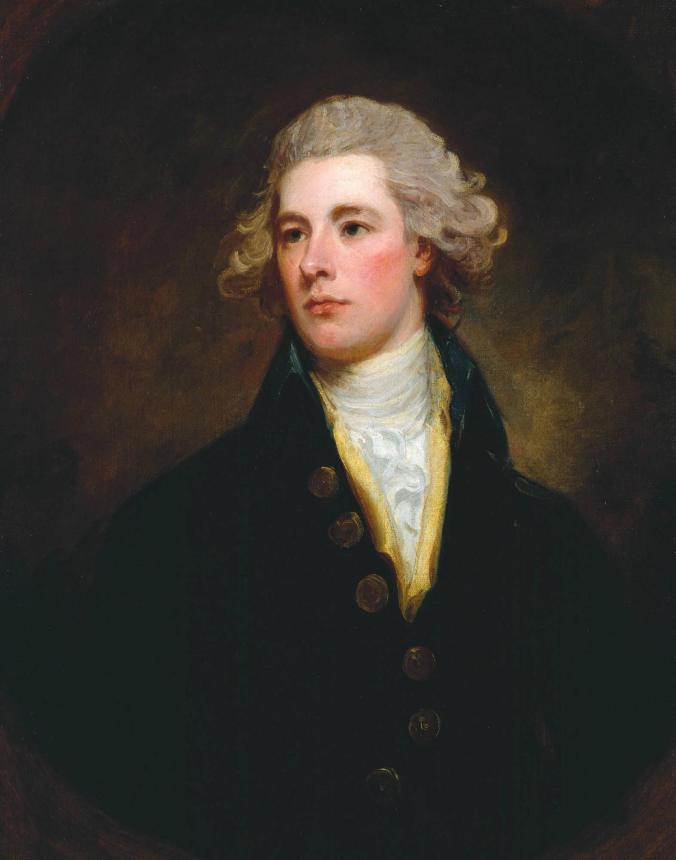

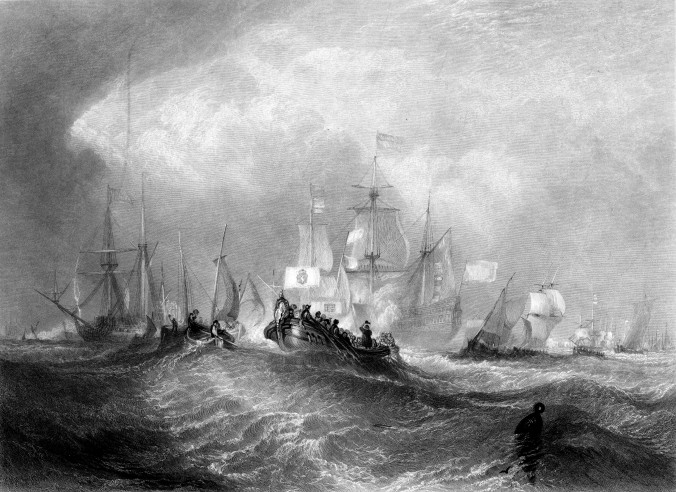

John Taylor’s adversary in the Federalist camp was the renowned Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton’s goal was to essentially turn the United States into an industrial and commercial power to rival any European nation. To accomplish task, Hamilton would pursue every avenue possible by advocating for a strong central government, creating reliable financial institutions such as the Bank of the United States, and even advocating for industrial espionage against Great Britain.

If Alexander Hamilton wanted to push America into an industrial future, Taylor would seek the opposite. He made a very familiar argument: if people gather more into cities, they will be susceptible to luxury and vice. This will cause the erosion of virtue and manly independence and bring about a decline of the Republic.

As such, Taylor became an implacable opponent of infrastructure projects such as the building of canals and roads which would contribute toward the industrialization of the nation. He also was a strong supporter of the States Rights movement, seeking to curtail the power of a seemingly dictatorial central government in order to protect the Southern farmer’s way of life from capitalist tyranny.