Picture this – James II, a Catholic monarch of a thoroughly Protestant England is forced to flee his kingdom for France, much in the manner his father Charles II had to at the outbreak of the English Civil War have a century earlier.

This is for all intents and purposes, a power struggle between a monarch subscribing to the idea of the Divine Right of Kings versus a Parliament seeking to expand its own power.

The Issue at Hand: Religion.

Since the time of Henry VIII, Catholicism had been always held in suspicion by the power holders within the British Isles. “Popery”was often associated with England’s most hated rivals – France and Spain. Furthermore, since the Bourbon monarch Louis XIV ruled France in an Absolutist manner, where power was directly centered upon the king, many within England considered Catholicism to be associated with arbitrary rule.

Although not quite political parties in the modern sense, the Tories and Whigs who comprised parliament had two specific fears:

- The Whigs believed that Catholic Absolutism would endanger Protestant Religion, Liberty, and Property.

- The Tories had similar fears, but these were complicated by a respect for the traditional authority of the Crown. However, they did seek a Unity of Church and State for the sake of Stability – which would ideally make the Monarch of England a member of the Church of England.

Look closely enough and one can see the seeds of Anglo-American Conservatism and Liberalism starting to form.

For his own part, James II did little to endear himself to either group. James attempts to secure Catholic emancipation alienated his original supporters in the Tory party, which feared that his actions would lead to the disestablishment of the Anglican Church.

In a bid to create his own power base, James II held a policy of religious toleration, hoping to forge his own party out of the Catholics and Nonconformists (ie: Protestants who didn’t “conform” to the Church of England). His Declaration of Indulgence, which would enshrine religious toleration across his kingdom, was seen as a direct stab at the heart of Anglican power.

What followed was perhaps some of the most heavy handed tactics for a peacetime monarch during his era. It seemed that James II was single-handedly attempting to turn back the clock, using his power as monarch to purge his opposition (usually Anglican Protestants) from within the government and military. They were of course replaced with people he could trust (usually Catholics).

This was the proverbial last straw. Tyranny and Arbitrary Rule seemed like a reality.

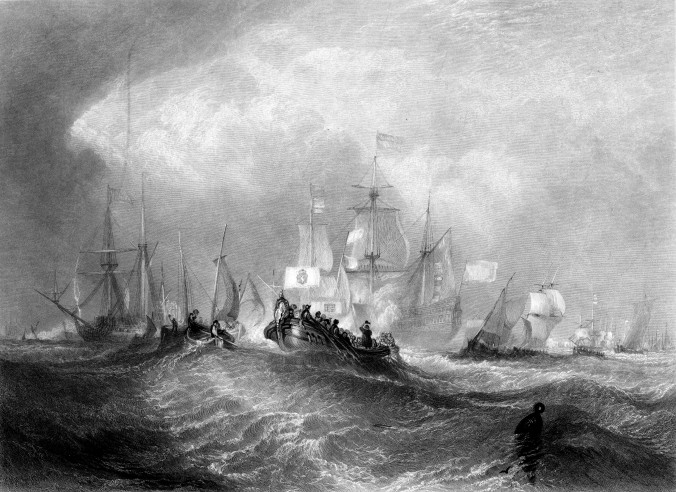

In November of 1688, William of Orange stadtholder of the Netherlands and husband to Mary Stuart (James’ daughter) crossed the North Sea with an army to England in an attempt to overthrow his father-in-law. William was a Protestant hero who valiantly fought alongside other Protestant monarchs against Louis XIV during the War of the Grand Alliance. As such, he was deemed a more preferable monarch to many factions within the British elite. And so a conspiracy was formed in order to finance William’s “invasion.”

The rest as they say is history – James II fled to France where to this day his descendants hold a claim to the throne of Great Britain. This event was commemorated as the Glorious Revolution, specifically because the amount of bloodshed during this transition of power was well below average.

Although William was obviously pleased by the outcome of events, he found that there was some…..interesting legislation waiting for his approval upon ascending the throne.

One such piece of legislation seemed obvious – the Act of Settlement of 1701 required the King of England to be a Protestant and could not marry a Catholic. This particular law was only recently amended by the Succession to the Crown Act of 2013.

Another law was rather self serving, as the Triennial Act of 1694 required that Parliament would meet every year and have elections every 3 years. Up until this time, only the King could have called Parliament to convene.

But of particular importance to history at large would be the Bill of Rights of 1689. The Bill of Rights essentially limited the power of the king, but demanding things such as no taxation by royal prerogative, freedom of speech in Parliament, habeas corpus, and the denial of cruel and unusual punishment for crimes.

To our American readers, this may all seem rather familiar as the American Bill of Rights of 1789 was modeled on the English one.

But what these chain of events concluded was that power was ultimately held by Parliament in the British Isles. And for the time being, the freedoms and stability held in common by both proto-Liberals and proto-Conservatives were safe.