Given my background in the natural sciences, I’m often interested whenever I run across a historical figure with intriguing medical conditions. So this round of Medical Matters will be devoted to the medical profile of a certain Mr. John Randolph of Roanoke – previously mentioned in Agrarian Doubts: States Rights and the Old South, where I tried to convey some of his eccentric qualities along with his passionate defense of the Southern agricultural way of life.

But what struck many of his colleagues in Congress was…..his looks. To quote a description of him at the time:

His head is small and until you approach him near enough too serve the premature and unhealthy wrinkles that have furrowed his face, you would say that it was boyish, but as your eye turns toward his extremities everything seems to be unnaturally stretched and protracted. To his short and meager body are attached long legs which, instead of diminishing, grow larger as they approach the floor until they end in a pair of feet broad and large, giving his whole person the appearance of a sort of pyramid… His voice is shrill and effeminate and occasionally broken low tones like those heard from dwarves and deformed people.

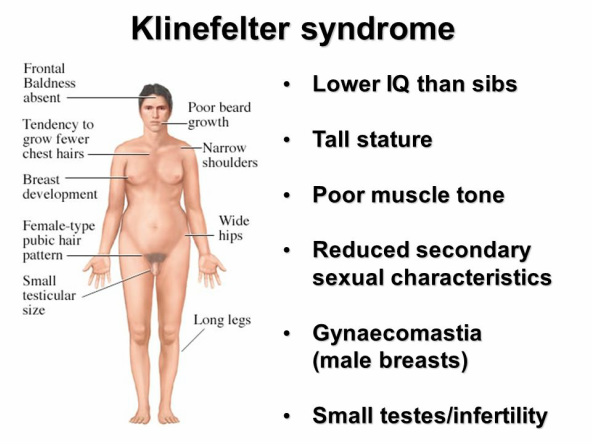

It is believed by some historians and modern day medical professional, that John Randolph may have had Klinefelter Syndrome.

Klinfelter Syndrome is caused by a meitotic nondisjunction event during cell division and the formation of gametes (egg and sperm cells). In the specific case of Klinefelters, an extra sex chromosome is present. Normal human beings have 46 Chromosomes – Men being XY and Women being XX. Klinefelters results in a person having 47 chromosomes – XXY.

The extra X chromosome can result in a variety of clinical manifestations as listed in the graphic above. It should be noted however that a person who has Klinefelter syndrome does not necessarily manifest -all- of the symptoms listed. But one common symptom that raises the suspicion for Klinefelter syndrome aside from body presentation is impotence brought on by a decreased production of testosterone due to testicular atrophy.

We know that John Randolph was in fact impotent. He was also beardless and had a pre-pubescent voice throughout his life.

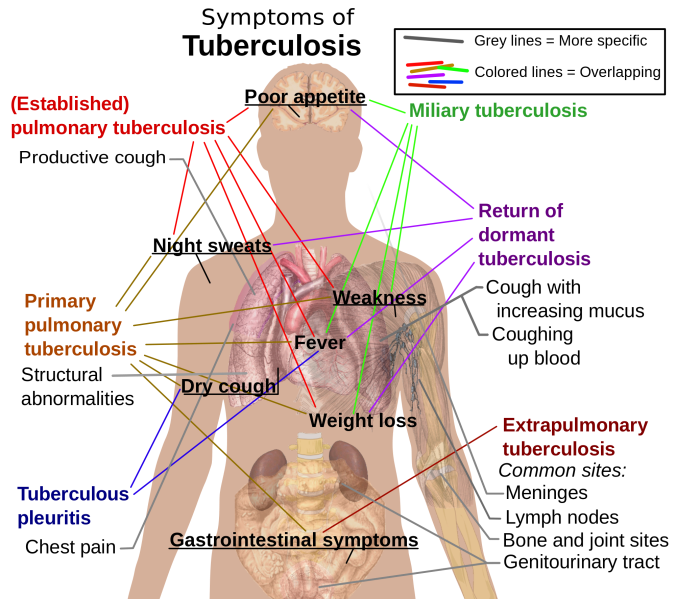

However we also know John Randolph was afflicted by tuberculosis at an early age. Tuberculosis is a mycobacterium which favors the lungs as a site of infection. However, TB can also infect the genital tract – which would result in damage and a halt to puberty. So it is also quite possible that Randolph actually never went through the biological stage of puberty – which would help in explaining his impotence.

Tuberculosis would also prove to be the cause of Mr. John Randolph’s death at the age 6o.