This segment of Agrarian Doubts is the culmination of our historical trip through the American South that forged a mix of cultural and political concerns into Southern Conservatism. While it is my intention to shift our focus back to Great Britain’s agrarian tradition in the future, we may yet again poke our heads into this region of the world.

Many would assume that given the trajectory of this series, the Civil War would have been the next topic to be covered. However, for our purposes it is what happened after the Civil War that matters more. Or rather, how the Civil War was remembered and memorialized by those who lost the struggle.

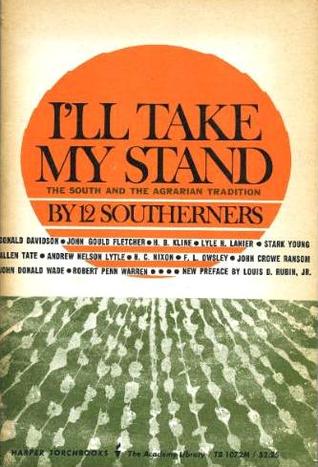

It may come as a surprise to some readers but during the 1920s when America was in the midst of unbridled economic prosperity – Southern Agrarianism found a voice once again. Or rather it found 12 voices. These men were not planters or farmers or soldiers. They were in fact a collection of novelists, writers, and poets based out of Vanderbilt University, who joined together to create a manifesto entitled I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition.

The primary concern of these writers was the growing industrialization of the South during the 1920s-30s. In their view, modern industrial capitalism was a dehumanizing force. This line of argument may have some resonance for the followers of Karl Marx, which is ironic given that the Southern Agrarians in a sense condemned both Communism and Capitalism as being Anti-Conservative. To quote a passage from the Introduction of I’ll Take My Stand:

We look upon the Communist menace as a menace indeed, but not as a Red one; because it is simply according to the blind drift of our industrial development to expect in America at last much the same economic system as that imposed upon Russia in 1917.

In place of the option of choosing either materialistic system, these intellectuals offered up the Antebellum agricultural model as the panacea and future of the South.

Their critics found that the Southern Agrarians understanding of their heritage was a bit too…..sentimental.

Take the issue of farming for instance. The essayist Andrew Lytle had written that “The farm is not a place to grow wealthy; it is a place to grow corn.” While these sentiments may be shared by our modern day Green and Organic food movements, economists and historians will be quick to point out that agriculture tends to bend away from subsistence farming toward cash crops. After all, we cannot forget that cotton was king in the Pre-Civil War South. The labor intensive nature of Cotton farming necessitated the use of slaves. The sale of cotton to Great Britain was also an important source of revenue for the aristocratic south.

Another Southern Agrarian and well-noted 20th century modernist writer Allen Tate attempted to live out the principles he advocated for. It is however, much easier to write about the joys of farming than to actually perform its duties. From what I gather, Mr. Tate had to hire a family to do the farm work. And it is no small point of irony, that Mr. Tate could only acquire his farm with the help of his brother…. who happened to be a successful banker.

It could be argued that the Southern Agrarians were constructing their worldviews from within the set of beliefs dubbed by social scientists and historians as the Lost Cause of the South. I believe this quotation from Wikipedia best summarizes this phenomenon:

The Legend of the Lost Cause began as mostly a literary expression of the despair of a bitter, defeated people over a lost identity. It was a landscape dotted with figures drawn mainly out of the past: the chivalric planter; the magnolia-scented Southern belle; the good, gray Confederate veteran, once a knight of the field and saddle; and obliging old Uncle Remus. All these, while quickly enveloped in a golden haze, became very real to the people of the South, who found the symbols useful in the reconstituting of their shattered civilization. They perpetuated the ideals of the Old South and brought a sense of comfort to the New.

-Yale Professor Roland Osterweis

This mytho-narrative arc perpetuated a few inaccuracies – the race relations between the African Americans and Caucasians in the Old South being a primary issue.

Several historians and writers have explored the idea of the Lost Cause of the South and came upon a fascinating conclusion – that this was all about national reconciliation.

The historian David Blight for instance noted a particularly intriguing trope in postwar fiction. A young, materialistic, and utterly rich Yankee man marries impoverished but spiritual Southern bride. He represents the power of industrialization and its brutality when unchained. She represents the chivalry and honor of a time long gone. Perhaps her social graces will be a civilizing influence on the young man.

Perceptive readers may notice similar themes brought up in a previous blog post, Agrarian Doubts: Sir Walter Scott and Trans-Atlantic Conservative Romanticism.

————————————————————————-

The legacy of the Southern Agrarians is rather mixed. Their “leader,” the scholar-poet John Crowe Ransom, grew disenchanted with the movement and publicly repudiated it in 1945.

I find an irony at my expense in remarking that the judgment just delivered by the Declaration of Potsdam against the German people is that they shall return to an agrarian economy. Once I should have thought there could have been no greater happiness for a people, but now I have no difficulty in seeing it for what it is meant to be: a heavy punishment. Technically it might be said to be an inhuman punishment, in the case where the people in the natural course of things have left the garden far behind.

The question, then, is this: of what value could the Nashville group’s thesis be to a people who had “left the garden far behind”? Would their argument serve no better purpose than to offer up ironies concerning a road not taken? Once the garden has been left behind, does the idealistic contemplation of it, even in art, become much more than a symptom of a neurotic urge to escape what lies ahead of the garden?

One of his colleagues Robert Penn Warren, the first poet laureate of the United States, eventually joined the civil rights movement and supported a variety of progressive causes -because- of his belief in agrarianism.

And for a certain few, the enthusiasm for the agrarian way of life has never died. Stark Young‘s cousin, Stephen Clay McGehee, actually runs a website called The Southern Agrarian – http://www.southernagrarian.com/. It is as one may expect – a website that touches on the practicalities of farming, southern culture, honoring the heroes and legacy of the Civil War, and religion.