In previous posts in the Agrarian Doubts series, we’ve noted the key platforms of the Jeffersonian Democrats understanding of the ideal American Republic. To list a few ideas:

- The Yeoman Farmer as an Exemplar of Virtue.

- A Suspicion of Expertise and Specialization.

- A dislike of concentrations of wealth and people, ie: Cities.

- Industrialization and Banking are disruptive societal forces.

- An Expansionistic Policy toward the West.

- A favoritism of Direct Democracy for all civic positions, including judges.

The populist flavor of these ideas cannot be overlooked. And as populist issues they have been featured as critical pieces of modern ideologies found on the Left and the Right in the 20th century. After all, the Maoist version of Communism would be just as accepting of many of the propositions stated above.

With the exception of the 6th point, many of these ideas were championed by the old Southern Aristocracy as part of a common agricultural world view. The internal logic that supports these issues was a respect for local tradition and social hierarchy colored by a romantic outlook on the agrarian way of life.

The political manifestation of these concerns and sentiments became a preoccupation with the notion of States Rights versus the Federalist (and later on the American Whig) Party’s attempts to create a much stronger central government that favored industrial economic interests.

This is a tension that existed right at the founding of the United States of America. Those in support of individual states retaining their sovereignty challenged policies by the central government at every turn. We saw this in Jefferson and Madison’s support of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 as a counter to the Federal government’s attempt to limit free speech and the immigration of European radicals via the Alien and Sedition Acts. What the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions essentially stated was that the individual states had the right to nullify legislation within their own boundaries when the Federal government passes a law that exceeds its stated powers.

We see this debate occurring again over the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Compromise dictated that new additions to the Union must be made in twos – 1 slave state and 1 free labor state in order to maintain the balance of power in Congress. John Taylor of Caroline wrote one of his infamous passionate pamphlets against this compromise, on the basis that the Federal government was essentially deciding on the particular labor laws of the state – a power that should only be reserved for the state governments alone.

And even when the Jeffersonian Democrats were initiating the purchase of the Louisiana Territories from Napoleonic France, Southern politicians like John Randolph of Roanoke would come to regret the actions of the party as it wasn’t clear if the President of the United States had the authority to make that purchase. This would lead to opposition against the acquisition of Florida from the Spanish crown a few years later.

The question over the nature of sovereignty and which political body had the right to arbitrate when a law exceeded the powers of a government almost came to a head during the Nullification Crisis of 1832. Prior to 1832, a number of tariffs were instituted to prevent European and British manufactured goods from driving Northern Industrialists out of business. The effect of the tariffs on the South, especially the Tariff of Abominations of 1828, would result in Southerners paying higher prices for manufactured goods and having their source of income via the cotton trade with Great Britain reduced.

South Carolina would not stand for this. The state government would go on to challenge Andrew Jackson’s administration on the matter by invoking the sovereignty of the states argument. South Carolina would go on to outlaw the tariff and build an army to defend itself. Jackson would not take this laying down however, and pushed the Force Bill through Congress which allowed the Federal government to retaliate against a nullifying state like South Carolina. It took all the skill of Kentucky Senator Henry Clay to broker a compromise that did not end in bloodshed.

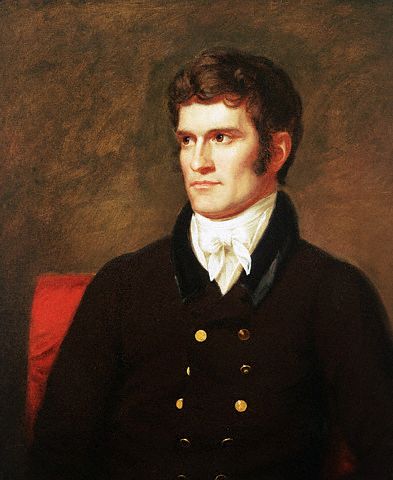

Incidentally, Andrew Jackson’s own Vice-President John C. Calhoun was a secret supporter of the Carolina cause and would go on to be a strong proponent for the nullification theory.

Calhoun elaborated his views on government in a treatise known as The Disquisition on Government. In this work, Calhoun makes a critical distinction in how voting majorities exist.

A numerical majority is merely the will of the more numerous amount of citizens imposing their views on the minority group. As such, an absolute majority will always prevail over minority interests. It is interesting to note that Calhoun’s conception matches the Tyranny of the Majority concept that classical liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill would warn against many years later.

A concurrent majority would require a compromise between the interests of the majority and minority groups. It would be in effect, a unanimous decision of all major interests within a community.

It should be noted that Calhoun’s idea of a minority does not correlate well with our modern conception of the word. What he was concerned about were in essence vested interests and privileges held by a propertied minority.

Calhoun also had a negative view on one of the founding principles delineated by the Declaration of Independence. In his mind, man was not born free and equal. Liberties enjoyed by the people were not a natural right, but rather granted by participation within a well-governed society. He was in effect rejecting the contract theory of government (Federal Power) in favor of the compact theory (State Sovereignty).